Welcome to All Rise

When one person rises, we All Rise.

After nearly 30 years of leading the treatment court movement, the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP) has rebranded as All Rise to better reflect our impact across the justice system.

Martin Sheen helps launch All Rise

A treatment court supporter for more than 25 years, Martin Sheen helped launch All Rise at RISE23 with a stirring message about the promise of justice system innovation.

Our Work

When communities rise to confront the challenges of our time, we All Rise.

Resources

We believe in a research-based approach to justice innovation.

Impact

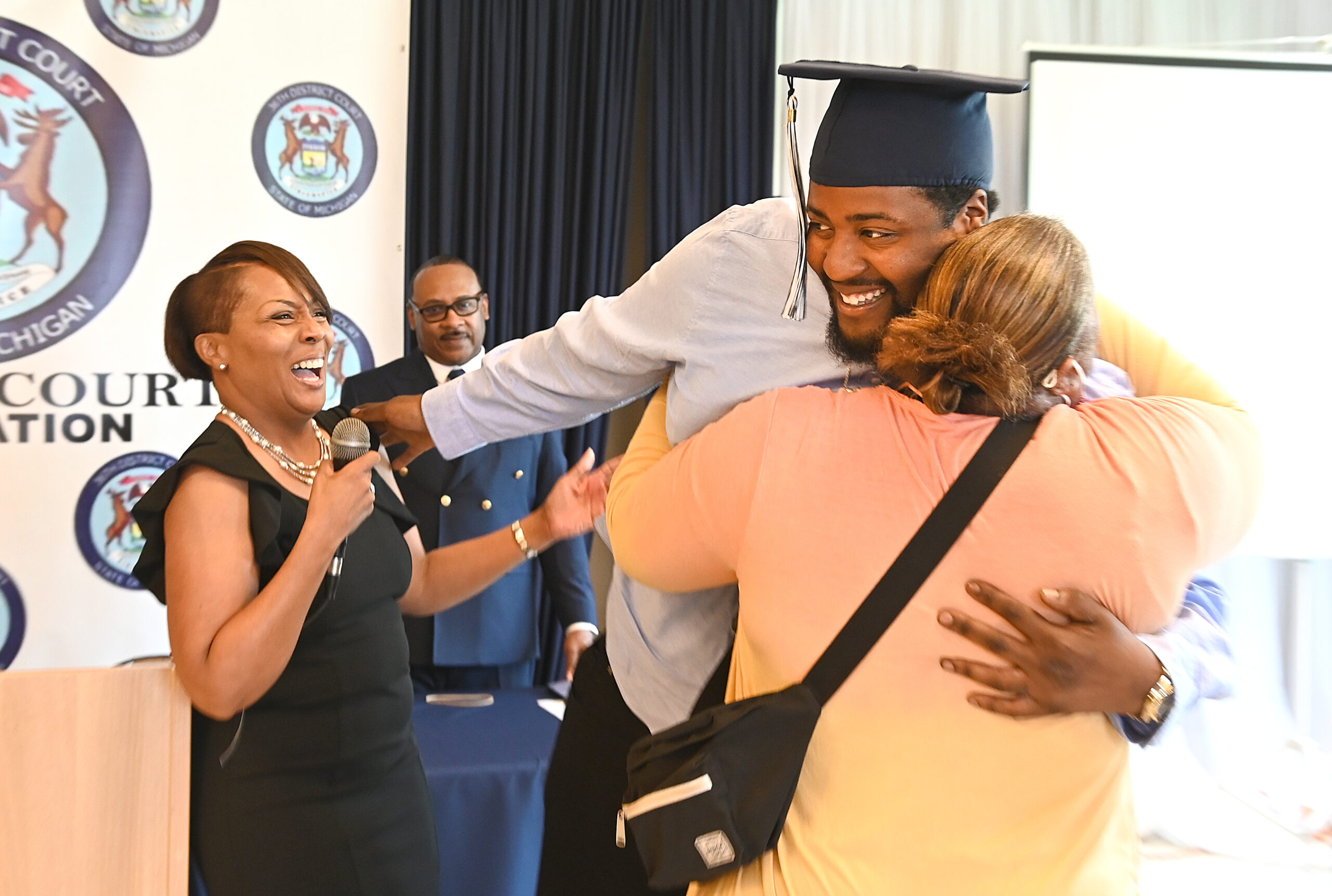

We have built a network of 4,000 treatment courts connecting approximately 150,000 people to treatment each year.

National Treatment Court Month

Each May, the treatment court community comes together to celebrate National Treatment Court Month. This is our annual opportunity to share our success, educate the public, and engage elected officials. Download your National Treatment Court Month Toolkit today!

Browse Our Resources

RISE: The Conference Event of the Year

Attendees

Speakers

Sessions

CLE/CEU Hours

RISE24

In May, we will continue our march toward ensuring every individual in the justice system has access to evidence-based treatment and recovery at RISE24.

Click below to visit the RISE website and learn more about the conference event of the year.

Advocacy

We fight every day for funding to support evidence-based justice reform. Learn how you can get involved.

Donate

Your support helps advance training for public health and public safety professionals serving people impacted by substance use and mental health disorders.